Oklahoma in the Spotlight: Sunrise Tippeconnie on the Art of Okie Films

Sunrise Tippeconnie on location in Oklahoma

Photograph by Zachary Burns

Oklahoma filmmaker Sunrise Tippeconnie has, throughout his decades-long filmmaking career, only had one job on a set that he’s truly disliked.

“I was a drapist on one commercial once — putting up curtains. You don’t think about how they get up,” Tippeconnie says. “They look nice, they work as curtains, but they’re very heavy and terrible to work with. That’s a department I do not want to have anything to do with.”

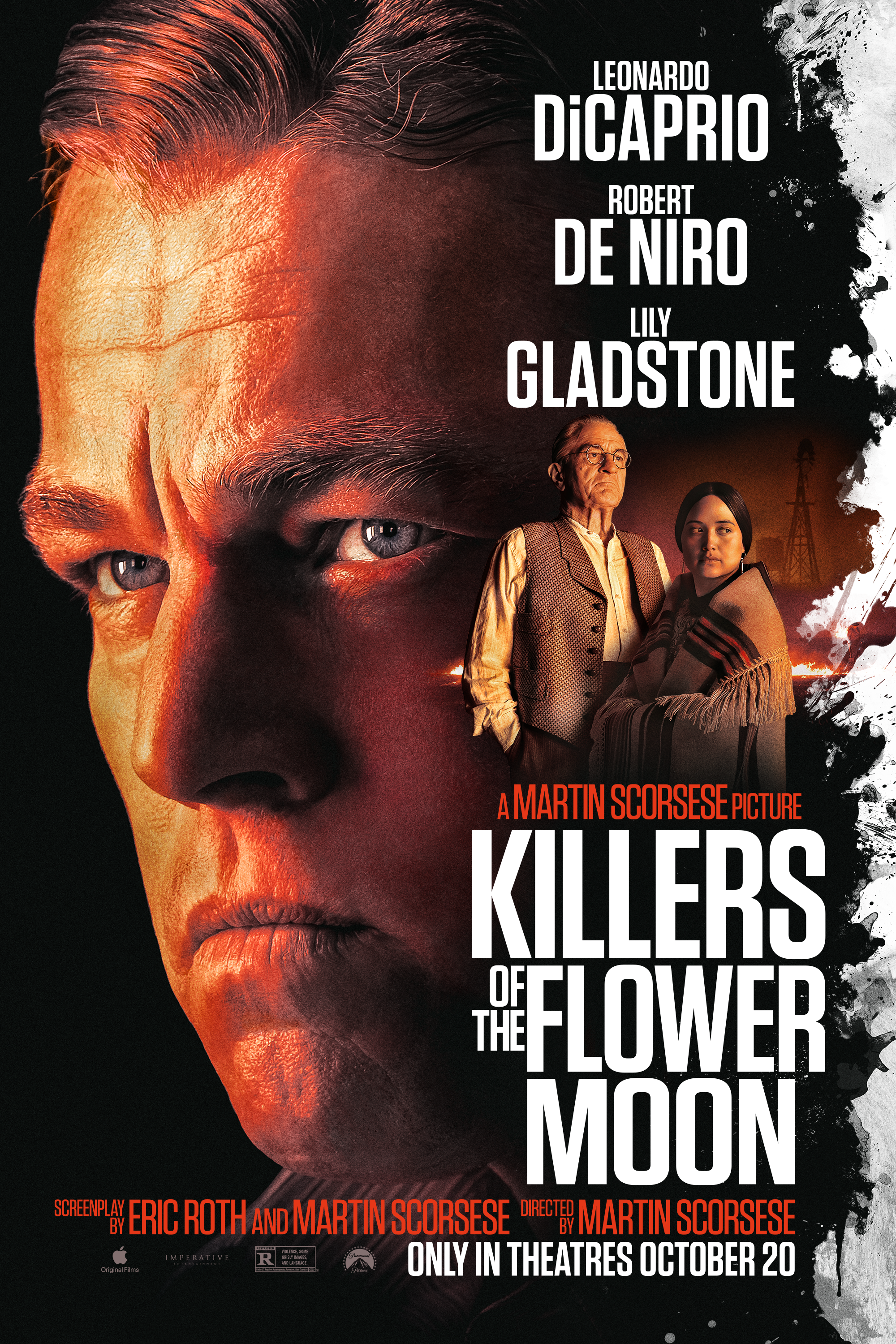

His willingness to explore almost every role on a film set has earned the Director of Programming for deadCenter Film Festival (DCFF) and part-time film lecturer some serious filmmaking chops and an IMDB page feet long, just recently having worked on Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, nominated for 10 Academy Awards, and 2021 Academy Awards frontrunner Minari.

But, despite the high-profile and out-of-state filmmaking opportunities on his resume, Tippeconnie always holds Oklahoma film close to his heart.

PULLING FOCUS

Tippeconnie tends to skirt the line of questioning about why he selected filmmaking as his career, but he does point to an experience in high school that influenced him. When an English teacher tasked the class with examining the movie Dead Poets Society for subtext, that was the first time he realized a film’s ability to convey something deeper.

“I was like, ‘Oh, this is really amazing that [a film] could reveal something to one person and someone else might be oblivious to it.’ That was intriguing enough for me to investigate what’s happening in a filmmaker’s body of work,” recalls Tippeconnie.

After early support of his interest in film, Tippeconnie entered the University of Oklahoma in the late 1990s as a dual Media Arts and Architecture major. Film captured his interest quickly, especially how light values work on screen to support the narrative and tone of a work. His obsession first started with the light meter, a tool used to measure light in film and photography.

“I felt like if I understood the light meter, I would understand [a film’s] subtext,” says Tippeconnie with a laugh. “It’s a magician’s tool — ‘learn the trick, you will figure out everything’ – which was not the case. But I became very proficient, technically. And then I started to work with other people and got hired on movies.”

Tippeconnie’s timing of selecting film as his creative outlet and his career couldn’t have been better. In 2001, The Oklahoma State Legislature enacted the Film Enhancement Rebate Program to incentivize film productions to shoot in Oklahoma and use local crew and talent.

Lily Gladstone with Martin Scorsese on the set of Killers of the Flower Moon

Originally, the rebate was rolled out as a response to the Canadian government’s 1995 film rebate program, but over its 20-plus-year existence, it has been retooled to compete with those of other states.Georgia, New Mexico and Louisiana are all power players in the film industry now, thanks to generous film rebates and continued investment in the infrastructure required to support productions with blockbuster budgets.

To remain as a competitive alternative, Oklahoma has been not-so-quietly retooling the rebate since 2005, increasing the annual reimbursement cap into the millions, where it is today. According to reporting by Oklahoma Voice, the current reimbursement cap for the Filmed In Oklahoma Act of 2021 is a pooled $30 million, which Lt. Gov. Matt Pinnell hopes to increase to $80 million after this upcoming legislative session.

It’s not hard to see the cause-and-effect of Tippeconnie’s involvement in bigger films tied to the simultaneous rise in the rebate cap. He’s hoping that a higher cap will help offer that opportunity to more prospective Oklahoma filmmakers in the next couple of decades.

“Right now, we’re probably in a place again of transition in Oklahoma. We’re going to develop and nurture some really great talent here,” says Tippeconnie. “But where the [rebate] cap is will start to limit the kinds of productions that will take advantage of those opportunities.”

Frame from Oklahoma-made silent film The Daughter of the Dawn

OKLAHOMA RISING

Tippeconnie’s support for Oklahoma’s film industry doesn’t stop when a director announces, “That’s a wrap.” Being appointed the Director of Programming for DCFF in 2023 — the first Indigenous person in the role —feels like a logical next step for him, a continuation of how he supports filmmakers, especially Okie-grown ones. Being in the leadership at DCFF comes with a significant responsibility, as it’s one of 193 festivals that can qualify filmmakers for the Academy Awards in short film categories, according to FilmFreeway.

But not all Oklahoma films make it into DCFF. What happens to those films that fall between the cracks, that never score widespread viewership, distribution or acclaim? What happens to those works?

Tippeconnie expresses hope for an archival and restoration initiative focusing on Oklahoma’s film scene. He extends his gratitude to the Oklahoma Historical Society for documenting and archiving some Oklahoma-made silent films (like The Daughter of the Dawn), historical films that include Theodore Roosevelt and the Abernathy boys, and Comanche chief Quanah Parker. But he also emphasizes the importance of extending this archival effort to more recent history.

“It would be great to be able to remaster films from the early period of Oklahoma filmmaking near the beginning of the millennium,” says Tippeconnie. “Money needs to be set aside for that as much as crew base development.”

Tippeconnie notes that as much as films like Twister attempt to understand and portray something about Oklahoma, they don’t truly capture the “Oklahoma-ness” of the state and end up being surface-level observations. (Tornadoes, “Boomer Sooner,” oil, football.)

But this tide is changing, especially regarding Indigenous stories centered in Oklahoma. Killers of the Flower Moon, shot in Pawhuska, may be one of the most prominent examples to date featuring historically accurate representations of Oklahoma and Indigenous people. Tippeconnie notes how the department heads on the film were deeply “interested in expressing” the story and understood what they were doing was an art form.

However, as he discussed in an interview for The Oklahoman regarding the film, Killers is one piece of a larger conversation surrounding accurate Indigenous representation in film.

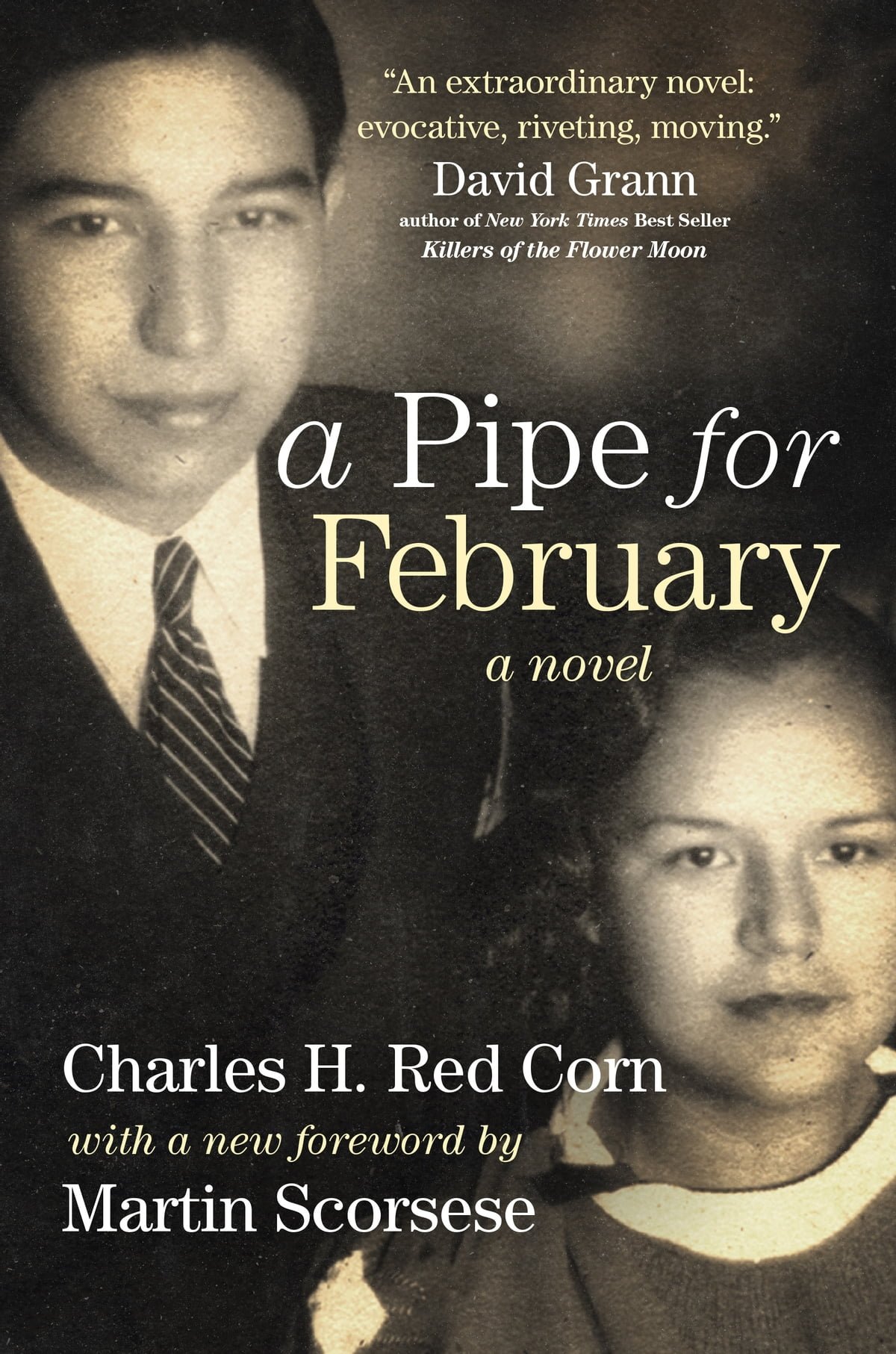

“That is pretty much how I think about the film, that it is incomplete in its voice. Especially knowing now that there is an Osage writer behind A Pipe For February,” Tippeconnie says, mentioning a historical novel set at the time of the Osage murders that Scorsese used as a source.

A key factor that often separates well-done and lackluster Indigenous representation in film is whether Indigenous people are above the line in leadership roles on a production. Tippeconnie holds up Hulu/FX’s “Reservation Dogs” (on which Tippeconnie also worked) as an excellent portrayal of what Indigenous life is like in Oklahoma. Led by Oklahoman Sterlin Harjo and Academy Award winner Taika Waititi, “Reservation Dogs” is the first film project with only Indigenous leadership at the helm and an all-native writers’ room.

But for projects already attached to a specific director or writer that feature Indigenous characters, bringing in individuals who serve as consultants can help authentically portray the culture on screen — and center the story from the Indigenous character’s perspective.

“The benefit of having someone from a culture working on a film about that culture gives such depth,” says Tippeconnie in a podcast interview for The Cinematropolis regarding his experience consulting on the 2022 Predatorprequel Prey, which centers around the Comanche Nation.

“Many audiences won’t see it. But the audiences that are of that background definitely will embrace it. I think that’s one reason why it’s so popular.”

As Indigenous-led and Oklahoma-centered projects continue to break into the mainstream, Tippeconnie is excited for not just his upcoming projects but other filmmakers’ projects he can continue to champion through outlets like deadCenter and his film criticism.

That desire to support and lift Oklahoma filmmakers is reflected in the one job that Tippeconnie hasn’t yet had in the film industry: being a distributor.

“What an amazing position to be able to be in. ‘I get to fight for this artist, and this vision that I’m pretty sure is of value, and the audience will prove us right’ — that’s an undervalued gamble,” says Tippeconnie. “There’s something to be said about that, that somebody’s willing to fight for art.” •

The Luxiere List: Oklahoma’s Film Syllabus

From the historically impactful to the odd to the grotesque, here are some of Sunrise Tippeconnie’s recommended Oklahoma-made films that understand the state and convey something authentically Okie.

“It’s important to understand what people have tried to do to get us where we are. And I would imagine a lot of techniques and filmmakers have resulted from these films.”

The Daughter of the Dawn (1920): A formerly lost silent film, shot entirely in Oklahoma with members of the Comanche and Kiowa tribes. Restored by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Stark Fear (1962): A black and white psychological horror movie created by Ned Hockman (who founded the OU film program) and Dwight V. Swain.

Terror at Tenkiller (1986): An ’80s slasher that “is not that great, but it’s a part of American independent cinema, the horror genre.” Directed by Ken Meyer.

Eye of God (1990): Tim Blake Nelson’s play-turned-film that “captures something about what Oklahoma is in terms of its small-town nature.”

Okie Noodling (2001): Documentary chronicling noodling for catfish, directed by Bradley Beesley.

Goodnight Irene - short (2005): Early work of director Sterlin Harjo that informs some of the characters on “Reservation Dogs.”

The Fearless Freaks (2005): Rockumentary chronicling the rise of The Flaming Lips, directed by Bradley Beesley.

Rainbow Around the Sun (2008): Rock opera and concept album that played at SXSW, directed by Kevin Ely and Beau Leland.

To the Wonder (2012): “The closest I think any non-Oklahoman has gotten to capturing Oklahoma is Terrence Malick in To the Wonder. Somehow, he’s captured something that other people have not.”